But to-night such moving sinewed dreams lie out

In darker fathoms, far beyond the head.

— Seamus Heaney, ‘Shore Woman’

I

In the sixteenth summer after my wife and I moved to the lighthouse, I started dreaming.

I saw the great hand of the ocean, slow and speculating. It scratched at the rock face, boulders dislodging as easily as flecks of sediment. Each teetered uncertainly for three beats of a slow-swinging pendulum, then stumbled with lopsided urgency towards the sea, a lumbering, then galloping, clink of shale-on-shale, rushing and rising like a drumbeat, a loud splendid crash picking apart the neatly stitched seams of the ocean, a trembling, greedy span of water rising up to swallow it whole, the strict tunnel of air down through the dark breathless blue. Then all was quiet again.

The body of the world rumbled in silent pleasure.

I stood smaller than a grain of sand, misplaced amidst this elemental earth. Behind me, a hill of weeping grass held home for a prophetic wind, whipping in a tight ring where the lighthouse would be built. It called like a beacon for the rains, trapped high in the atmospheric clouds, and set them dancing free upon the world.

I dreamt of the prehistoric, when the shape of the earth itself was malleable. The great palm of the ocean moved towards me like the slow hand of a clock, and raised one finger to beckon. I could not move. I stayed bound to the solid ground, far from the livid waters. It stretched open a broad palm, connecting with the edge of the land I stood upon like a causeway across the early sea. It tilted softly towards me, offering a venture forth. These hands that had carved out trembling passages in the world and shaped cliff faces to its liking now beckoned me forth for its next creation. I would not move.

My feet had grown into the earth. Ankles sprouting from the soft heft of soil, I sank through the sediment as the hand retracted with sorrowful slowness. Even when I was waist deep, I found in myself only a profound relief that the ocean had not taken me to become a part of its bidding. I could not face the waves lurking beneath its surface, always ready to break, hated its violent, heaving breaths chasing the moon between the shores. Its unsteady, roiling changes frightened me, and I could only thank that the earth still stood solid against its advances.

And in one yawning second of the storm, the hand of the ocean burst into a million fractal waves. Bright thunder broke—all became dark. The earth ate me like a seed.

***

Amina and Albert. She called me mila for the silly way it rolled off her tongue in the morning, mila mila mila like the plovers piping by the beach. We’d met a few years after university, working in the Natural Resources Department of the same development firm. In the artifice of the dinghy basement light, we specialised in categorising land types—partly by the ease with which it could be turned into a concrete foundation, partly by the number of legal loopholes we’d be required to jump through in order to build something on it. Neither of us was particularly enraptured by our work, but it made enough money to sustain a sizeable two-person loft in the city. We found a rhythm for domesticity early on, shared a love of cataloguing the ferries and mariners’ boats and cruises from our window, spending quiet hours in the early morning harbour light. Some people in the office teased us for this quasi-co-dependence, but we never paid them much heed.

Fifteen months into this steady exchange of parts of ourselves, we looked at each other across the narrow, rickety countertop in our apartment, and Amina smiled as sunlight cupped the back of her ear. Would you like to get married? she said with an air of faint inquisitiveness. A breeze ran like light through the slight flutter of her fingers. It was a beautiful morning, and the love I felt made me bodiless.

Her family and a few friends of ours came to the courthouse to watch us get married, and we both quit our jobs a month or so after. Around this time, I had been seized by a desperate sickness of the city—I caught sight of a film of smog, gathered at the bottom of the window sill of our bedroom, and had to sit down for the nausea that rose in my throat. Amina watched me curl into a chair with a tilt of her head and a slow blink, before saying we could do pretty well in a lighthouse. So we moved.

She tended an allotment, sheltered from the worst of the seawinds by the lighthouse. There, we grew potatoes, yams, Kakadu plums, gooseberries, pumpkins, and six types of squash. We had two goats, whom Amina had reared from foals: one was Jericho, a mottled brown and white specimen who tried to run free by ramming her horns against the fence post. We named her such because in her early years, she had a habit of marching tirelessly around the inner perimeter of her pen, bleating to the high heavens. The other goat was Milady, a tame and placid fellow. He spent most of his time pulling grass lazily from the earth and chewing it, mouth moving in languid circles. He was not so old for a goat, but had the comforting mannerisms of one approaching senility. We kept them for love and not much else, since Jericho only gave us milk on the rare occasions she felt civil enough to hold still beneath our hands for more than a minute. Even less could be said of Milady.

***

For two weeks of December every year, after a relentless sun had baked the dirt dry, a silent contingent of cicada nymphs weaned their way from the blasted earth around the lighthouse. They drew stealthily ever closer to the ash, pine and oak, holding the land like a guerrilla force, weaving deftly in and out of rock and root. They shimmied up those spindly silver-brown branches like a peeling river of wings, moulted, and launched their vocal pillage against the fortress of silent, coastal air. Every possible surface of the ground would crunch beneath our feet for weeks afterwards, littered with their old skins.

There was one season, in the second year after we had moved in, which Amina and I unaffectionately branded ‘the night of the thousand cicadas’. In reality, it was a string of nights—four weeks on end. We could barely sleep for the loudness of the dark. From the rushes of silvergrass and the dotted clusters of pine on our hill came a sweeping tide, ebbing in and out as though every piece of bark breathed and made its violent appeal to the gods of the air.

Amina and I were frequently cranky at each other in that month. I would stumble awake after forty minutes of sleep, and she would mutter tersely, welcome back, mila, always wide awake and brooding by the window, as if my inability to stay asleep against the warring chorus was a personal slight against her. I would mumble a quiet apology, my sorry sliced neatly in half by another wave of high-pitched clicks flooding high into the air.

I would retreat to the lantern room at the top of the lighthouse, where the thickness of the storm panes made it our only reliable stronghold against the sound. Ears ringing against the abrupt cessation of noise, I would rest my forehead against the window and attune my eyes to the shades of darkness which differentiated parts of the night: where the blurry line of trees occupied the distance. Where the land fell sharply into the sea. The jagged thought of a line cutting a lightless field.

It was a race to rediscover that perfect border every time the light from the lantern dragged across my side of the lighthouse, a blinding sweep that would briefly sear the world white. In those few seconds, everything fell out of—and into—order. A camera obscura world: my silhouette and my shadow were negative space, cut from the glass of the lantern room, projecting some divine, inverted vision of the world onto waiting land. Let there be light, and let it pass through me. Fire and pine. Noise and ash. A tentative division between dirt and water, this thin darkness like a trail of ants towards an anthill in the infinite distance. All this pressed against a plane of sudden, bright revelation.

Sometimes, when my eyes failed to adjust quickly enough, I wouldn’t catch where the land split from water, and I would be suspended in a unity of matter. There, every bit of darkness was as treacherous as the next. Only the tightness of the room around me was known: everything else was primordial water. It became a spiritual fear for me, a psychosis of belief that probably stemmed from the prolonged sleep deprivation. Cicada calls like a phantom limb in my ears, I would sink against the glass, and kneel in the likeness of prayer on the only stable ground in the world.

Amina sometimes braved the garden during those sleepless nights, driving herself deeper into the sound on a bite of pure spite; even Jericho went quiet, awed by how every inch of night had grown violent with noise. Milady barely minded it, knees folded beneath his body as his eyes flickered lazily open and closed. Tending to the nets over the gooseberry bush, Amina said she would glimpse sights of me, pressed against the glass as the lantern flashed behind, a cut-out silhouette against a halo of light. Like a bug, mila, she’d say. Caught in resin.

I never told her about the fear that gnawed at the base of my throat that summer, or the rush of adrenaline so strong I could feel it pass through the tips of my fingers into the glass. The second-by-second race where I’d test my eyes against the conspiring night was a private, guilty affair. Amina had always been the more grounded of the two of us, each foot planted staunchly in the world of what was actual. That summer, I never felt more distant, as she wandered amidst the herbs of the garden and I breathed unevenly in the lantern room at the top of the lighthouse, always seconds away from rapture.

II

Every so often, we’d rent out one of the lower rooms of the lighthouse to an artist in residence, for no more than three months at a time. We’d once had a man who wanted to map the length of the coastline with colonia-era surveying techniques. The lighthouse was basically a launching-off point for him; he’d set off for weeks at a time with a hiking bag that absolutely dwarfed him in size. It was always when we were mere hours away from sending out a distress signal, when we’d say tomorrow morning, we’re calling a search crew, that he’d reappear, healthy and hale, with huge scrolls of maps in his hand, and take an extensive shower that would deplete our hot water tank for at least three days.

There was another resident a few years later, a geologist studying the composition of cliff rock. She had an unparalleled dedication to field work: she would wake early in the morning, be hammering a piton into the cliff-edge by the time the sun came up, and would be rappelling down the cliff-face to collect samples before Amina and I had even woken up properly. This was her daily routine, regardless of the weather—once, we had to rush out in a panic amid a thunderstorm, and drag her, spluttering with a mouth full of seawater from some rogue wave that had slammed her body into the rock, back to safety. When she was dry and warm enough to be intelligible through the chattering of her teeth, the first thing she told us about was a rare fossil of an Ordovician trilobite she’d been in the process of excavating. Her primary concern was whether her bodily slam dislodged the arthropod. Our coast was rich with Gondwanan fossils, apparently so rare that they were worth risking one’s life for.

In the sixteenth summer after Amina and I moved to the lighthouse, our artist-in-residence was a spirited sculptor with the most delicate wrists I had seen on a person, who went by Cast in Relief. He refused to reveal whether that was more of an artistic pseudonym or some kind of legal adaptation. I suggested calling him CIR, pronounced with a hard ‘c’: Amina gave that idea a disapproving look, but mainly tried to say his name very quickly so that the last two words blurred and mangled together. I approximated the sound she made as something close to Castirlf.

***

Summer puts on a peculiar shade of unloveability when it becomes hot enough that one step outside is punished by a full back of sweat. Every inch of touch, contact between any two things, anything that broaches the thin film of separation around your body, becomes almost unthinkable. The cotton of the sheets becomes a maze of what is acceptable to touch: what part has been warmed by a body, already? What part no longer wants you? I would stand in the middle of the room, stifled by every fabric and every surface, though they stood metres away from me. All I could really hope for—and want, and deserve—at these times, was a cool wind through the window. Amina had no such inhibitions.

Amina would want, and I would follow her, as I would follow her beyond the pale of any sea. A body no longer felt like a fearful thing to have when I could hold onto it for someone else. My inhabiting it could be a service, until the next time they wanted it. Or no—that was not quite how it felt. That was how I would think about sex with Amina afterwards, when she had left the room to get water or to grab a snack or to air out the lighthouse, and I was stuck feeling the slick of sweat between my skin and our high-thread count sheets, which Amina insisted on buying for the softness. To have my body returned to my full possession never felt quite right.

In my dreams, that sixteenth summer, I always felt like I did in the aftermath of sex, like a beached whale on a changed shore. Like I had crawled off into the waters a million years ago, and come back to realise that not only had the contours of the cliffs changed, but entire species of crawling mammals and the plants they propagated had died out. A beached whale, ugly and pulled from its home, one bulbous eye smattered at the bottom with grains of sand. In these dreams, the bloated heaviness of damp clothing clung uncomfortably to my shoulders, and the cruel press of small pebbles against my skin made me all the more aware of the consequences of having a body. My ribs and my arms felt horribly out of place in the world, exposed to the slow weathering of the elements.

I saw a book once, Stages of Rot. In its great, green sky, an alien whale was hunted and brought down, each piece of its body unfolding and decaying over grand aeons to foster new life. At its heart was a pilot, taken to be displayed by the hunters who killed the whale. A whale song called her home. At times, I imagined myself wearing the serene, distant gaze of her face, contained within her glass enclosure. To be stuck in one place for so long—I don’t know if I would have dared to leave it after spending so many years there. Even if it was against my nature, even if I had been caught there by some force beyond me, I’m not sure whether I would want to leave. To rejoin the great body of a whale, to live and die within it; to slowly die, and rot, and change, into new, unknown, fearful forms of life.

Sometimes the hand of the ocean’s great body reached out to me again: it would always approach so slowly and patiently, and withdraw with such grief, that my heart became trapped halfway between guilt and fear, beating a tender hole in my chest. I don’t know how I would have articulated my refusal, had the ocean asked. It was not a fear of water, per se—there was just so much to the ocean that we could never know. Everything on land could be seen, could be touched. So much of it was recorded, and identified, and classified. Everything had an order, a place, a neatness and controllability to it. You might not be able to tame or domesticate it, but you could know it. You could know to avoid large pieces of driftwood amidst the grass, for the carpet pythons that might be coiled beneath them. You could know to watch for bluebottles along the stretch of wet sand left behind by the high tide. The rhythms of the ocean were far more unknown, ran on deeper timescales, kept themselves far from documents and lights.

When the dreams were not about the hand of the ocean, I would be lying on my side amidst the tall grasses on the cliff, and listening to the creaking of the earth like the falling apart of an old, old house. A sound I associated with the crashing of waves would echo from the ground, and the weeds I lay on would respond with a tremor. It would always be late sunset—I could tell by the growing coldness in the colour of the world around me, grasses veering on grey and not the rich green of the late afternoon. The horizon itself was covered by an upwards tilt in the overhang, the sun a bleary smudge of light from behind the crag.

The world in front of me would be spliced by the division between wilting summer grass—their blades sharp and dry but rough against the winds—and the encroaching, deepening indigo of night. When the sun finally set, I knew it would all blur together: the land, the sea, the night, all one uncontainable, dark blue. I would be suspended in between, drifting downwards through the masses of colour to the distant seabed.

The dream would always go the same: at first, a thin line of inkier blackness thickening on top of the green, as if the sun was merely setting faster and night had finally arrived. I would lie on my side, cold and wearied, frustrated and frightened that I had not moved, and yet far too tired to. This new darkness would seep across the division of land and sky like an oil spill. The earth would rumble and groan again. I would realise again and again, every time, always forgetting in between, that this new darkness was not a darker shade of night, or the ocean rising above the horizon. Those two distant blues would stay in their place—it was the rocks of the promontory I laid on that were falling away, with the creaks and quivers of a building being demolished, crumbling into the ocean.

I could feel the rocks of the promontory come apart, right beneath my cheek. I could feel the striking uppercut of cold ocean air, as solid ground broke from under my body, and I tumbled forward, falling endlessly, crashing like a cliff face into the body of the world.

***

CIR and I settled into a mutual enmity within the first week: he had installed his clay workshop in the middle of our kitchen, insisting that it, in his words, embodied the energy of the terrain, and would leave smudges of chalk over the wooden cupboard doors and on the backs of our woven dining chairs. I would make a show out of wiping them off meticulously with a damp cloth, right in front of him as he whirred a pottery wheel with easy confidence. The next time, I’d come down to a loud clattering through the drawers, and find the spoons, knives, and forks all thoroughly mixed across their three different boxes.

I swore there was a smugness on his face in those moments, as he kept his eyes resolutely on the vase or the bowl or the imitation of water splashing that he was in the process of carving, but Amina insisted that was my imagination. There was a brash confidence in the way he spoke and acted, as if challenging the world to step up and accept the terms of his existence, from the slight drawl and lethargy of his speech to the easiness with which he took up space—or the objectively, heinously bad pieces he sculpted (this was not just my opinion; Amina, a heartfelt defender of ‘contemporary’ art, agreed with me). He stepped lightly into dreams of greatness, easy in his statements of oh, I’ll be off to New York in the summer—there’s exhibitions, and I’m sure there’ll be somewhere to display.

Occasionally, CIR would enter a fit of despair, torn with indecision and dissatisfaction at his creations, and lie face down on the kitchen floor for hours. We had to step around him to cook and clean, and no amount of movement around him would prompt any reaction. The temptation to kick him in these moments was endless. Once, after I had almost dropped first a jar of sourdough starter, then the pan for the sourdough, then the sourdough itself by tripping over CIR, I crouched down very resolutely to ask: what the fuck is wrong with you? He had the gall to tilt up his head and look genuinely surprised. You could have just asked me to move.

To me, these outbursts seemed childish, moronic, and endlessly egocentric; Amina always seemed to face them with a wry amusement.

Sometimes he would clutter up the kitchen with so much noise and so much energy and so much stuff that I’d have to leave the lighthouse entirely and go stand in the goat pen, staring angrily at Jericho as she bleated indignantly from the fence post. No, I wish I could ram him out of the house too, Jericho. No, that wouldn’t be the polite thing to do, though, I agree. No, I can’t quite put my finger on why I don’t like him, either. Milady would try to rest his agreeable head on my knee. I didn’t like that the grass would sometimes dribble from his mouth onto my lap, but I would let him do so anyway. He would grumble quietly, slightly like a cat, when scratched behind the horns.

***

You should try to talk to him more, Amina suggested. I made the beginnings of a petulant protest. The two of you are quite similar, actually.

What do you even like about him?

She tilted her head. He’s quite settled in himself. He’s very honest about who he is and who he wants to be—I didn’t mention the fact that both these selves of CIR’s were really quite dislikeable—as much as you might dislike both of those elements. He wouldn’t apologise for being how he is.

And that’s how we’re similar?

No, it’s the most different thing about you. She smiled in that quiet way of hers. You’re quite similar because you’re both too stubborn for your own good.

***

I went out on a sailing boat, once, as a child—a tour boat that my family had booked for dolphin-watching. As we swung out from the bay into open ocean, a rogue wave hit us on the port side, and I was tossed clean across half the deck. My mouth was flung wide to cry before I could even process what had happened.

Half-cross, half-comforting, my father dragged me up by the hand, trying to make a joke out of it. It isn’t that bad, Albert, just plant your feet next time, like this like this, look—no, Albert, quiet down. Just like this. That’s right. You’ve just gotta get your sea legs. I tried to stop crying for his sake, but could only do so by suppressing it into a series of violent, crescendoing hiccups, the last of which would set me off into another string of tears.

My parents, sick of my histrionics within the first hour, were half-hearted in their attempts to cajole me into better spirits. Look at the dolphins! they said, eyes already caught behind their own cameras. I peeped over the side of the boat to watch the watery rinse of their backs nudge out of the ocean. They were not as cute as the pictures made them seem: solo waves, with minds of their own, cutting through the regular lattice of the tide. They would rush towards the boat in a swift pod, thin trail running through the water so that it seemed like the ocean itself was trying to jam into us from either side. I could see the trail of grey, clamping inwards on the boat, and I could feel, in the lurching of my stomach, that in the next second, in the next flash of their backs out of the water, we would be met with a slam into the side of our boat, capsizing us.

I scrambled down to lie flat in the boat, held onto the closest thing beside me—a wet, rough, sailor’s rope, as wide as my hand—and clamp my eyes shut. I stopped breathing. Waiting, holding, as the second split in half, then in quarters, then in eights, refracting into smaller and smaller units; I was so certain that each fraction of the second would be the last. There was a scoff above me. Get up, Albert, came the sharp reprimand. What are you doing down there? Stop being silly. I stood, so sure of dying. I peered over the side. The dolphins had swerved away, or deep into the water below us, leaving only a joyful swirl of bubbles behind them. The ease with which they inhabited the water felt like a joke.

***

The night of the thousand cicadas returned.

CIR smashed an increasing number of clay creations and chiselled with an agitated aggression. One night, about a week into the season, he lay his head down on the table with a loud groan, and beseeched me and Amina with tortured eyes: can’t we just kill them all?

No, Amina retorted instantly. With a sharpness in her movements, she stormed up the stairs. She seemed to leave even the world outside more silent as she ascended. I followed, after giving CIR a curt, victorious nod. Amina was in the process of getting into bed when I entered the bedroom, her back turned away from me, untucking the sheets with exaggerated viciousness. I was wrong, she said. He’s nothing like you.

I didn’t want to disturb this cocoon of peace that we’d briefly managed to salvage by asking why, so I washed quickly and laid on the bed, tossing the blankets off my body entirely and lying with my arms slightly outwards, but not so much that I could reach Amina, because the staunch heat of summer was particularly oppressive at night. I tried to sleep. I felt a rustling in the dark, then Amina’s fingers draping across the back of my hand. They’re periodical cicadas, I think. Her voice drifted like bubbles, rising to pop quietly on the ceiling. They only come out every 13 or 17 or so years. It’s really quite remarkable, how they manage to time it to throw off any predators. There was a glint in my periphery, maybe the moonlight or the slow blinking of Amina’s eyes. That noise is the sound of a whole new generation. It’s their first time above the ground in almost two decades. There’s no sound like it in the world.

CIR left soon after, but not before making amends. He began cleaning up after himself in the kitchen, and started making meals at more reasonable hours. Three days after the incident, he gifted a goat to Amina, which she named Forgiveness. Forgiveness was slightly lame, for no discernible reason. Still, we cleaned her hoofs and horns fastidiously every day, and were even appropriately dejected when she managed to run away.

III

After CIR left, I dreamt more often. The dreams would arrive suddenly, and eventually they began to creep out of their nighttime domain and into the humidity of the afternoon. Sitting on the couch of the living room, drowsy with the thought of a nap, I would fall back into unconsciousness and dream myself landing in the middle of open water, held in the palm of the ocean. Its great fingers would tower above like pillars in the middle of collapse, then fold, fold, clasp shut over my mouth, and I would be in a sudden shock of water, and I would blink awake, sweating and a book still open in my lap. The summer heat sometimes dragged the distant edges of the world into the unreal, blurring the copse of ash in the distance into a mirage of grey and green. Shakily, I would sip water from the sink, starkly sweet against the violent wash of salt in my dreams.

I would join Amina in the garden, helping veil the plum tree in a mosquito net so the birds could not plunder our spoils. I eyed the birds with great suspicion as they sat in squat bundles along the trees, screaming with great dissatisfaction at the fruits of our labour, now taken from them: each was a stealthy consort of the water, wheeling above the uncertain terrain of my dreams. Those thieving miscreants were a raucous addition to the cicadas, which remained as strong as ever, throwing themselves against the eclipsing heat.

***

This night was marked by silence. Sometime between dusk and the complete setting of the sun, a murmur had swept through the cicadas and they had, seized by a sudden collective will, shut up. The quiet arrived suddenly, like the eye of a storm I hadn’t realised was raging. When would the eyewall on the other side arrive? What would it bring with it once it hit? I fretted around the kitchen while Amina roasted some tomatoes that had finally ripened from the vines. I opened the window to a warm wash of air and felt the rush of an urge to scream out the window, to try to produce an echo in the stolid structure of disquieting summer air. Were we trapped in some invisible glass dome, oxygen draining out, the sudden muteness of the cicadas meant to be our first warning? Dark blue like a wall of water was rising in the distance, and—had the heat finally tipped over the edge of tolerance and knocked them all dead? The highlands, made brown and silver with a litany of carapace-corpses; bugs die, and other bugs eat them. I could not tell what had happened, and went to help with dinner instead.

***

I woke to lightning. A summer storm, cutting like a scythe through the mugginess of hot air, gathering it to set out from the clouds later, bit by bit. Rain fell like a fleet of arrows against the window, and I rushed upstairs to make sure the signal light had been turned on, as if it could save any mariner unlucky enough to venture out tonight. Rain fell in such steady sheets that the glass was a riverbank, the backing of a flattened waterfall. Whether the bright light of the lantern could pierce through the thickness of this ocean-on-land was uncertain.

Down the steep face of the lighthouse and mudfields away, I heard Jericho’s bleating. I stilled as it cut off sharply at one particular flash of lightning; it resumed, with a triumphant tone, a second later, lost amidst the gurgling crack of thunder. There was the clop of her hooves against the rotting wood, the fence breaking apart softly, and then she was off, across the promontory. I raced down the stairs. Amina was still soundly asleep in the bedroom, a soft snore and a furrow between her brows, which I stopped to smooth out. I held no particular affection for Jericho, but she was undoubtedly the creature for which Amina felt the most affinity, and I would gladly rescue the wretched creature for her.

Stashed in the engine room were a pair of rainboots we shared. A flimsy raincoat hung above them, thin enough to tear from a wayward branch and liable to slip off my head, leaving me to be drenched, at any second. I put it on, Jericho’s triumphant chorus already far further away than before.

I stumbled out of the house, body tugged back and forth by the sudden turning of air currents twisting the sheets of rain into a suffocating fabric of water. On the ground, the slow illumination of the world as the lantern revolved in the signal room was far more sinister. I would rush forward, mapping the land as it came into view, then stumble blindly through the imprint the light left on my eyelids as it disappeared: a mite, drowning in waves it could not see, glistening in colours beyond its field of vision. The heavy wash of rain insulated the sound of the wider world, like I was caught in a box, lid left open so I could marvel at the unmerciful sky.

Jericho seemed sure of her footing through this treacherous darkness—I followed her bleating best as I could, in the faint trickles of sound through the storm. She was going to the shore: I knew her hooves could handle the rocks on the promontory, slippery though they would be with the rain. I did not know if the waves would be high enough to drag her out to sea.

I was nearing the edge of the promontory, Jericho only a few footsteps ahead. I readied my arms to grab her torso—there would likely only be one chance to try and pick her up, as she scampered happily from side to side with great leaps and bounds through the slick mud. A distinctly salty spray of water hit my face; the light from the lantern room swung around, in time with a bright clap of lightning, and a hand of water reached out as a great wave broke against the cliff. Five watery prongs shuddered across the land. Jericho came to a stop in brief shock, just long enough for me to grab a hold of her, and her ears twitched against the bottom of my chin as the thunder broke a few seconds later.

We’ll need to fix your fence, I reprimanded her. She gave a haughty toss of her head, body still quivering as if the atmosphere’s pent energy was stored in the rapid trembling of her heart. Amina will be mad, won’t she? I scratched behind her ears. The lantern swept around again, and droplets from another wave fell against the edge of the cliff like weak fingers grasping at tufts of grass. For a wave of that size, it was so quiet. How strange.

I walked closer to peer over the edge of the cliff. My bones felt sodden, despite the warmth in the cloying air. In the far-off tree line, a lone cicada started to shriek. Lightning cracked over the open water. With an impetuous buck of her hind legs, Jericho leapt out of my arms, and I teetered like a fleck of sediment, like the clink of shale-on-shale, on the edge of the cliff. For a moment, all was still, and every wind and wave was as it was at the start of the world, wreaking feckless, primordial chaos across the land.

Then I was falling, and I was in water.

***

I woke to sun on my face, and a mouth half-full of salt. Even after spluttering it out, it lingered at the back of my throat, a painful prickling as I tried to look around me. The world was water, and I was the sole creature on this blue earth, floundering in the unknown. I was so alone. There wasn’t a headland in sight, or a cloud passing through the sky, or any hint of the violence that had shaken the world the day before.

From the limited life-saving training we’d been given in school, I knew that lying on my back would keep me alive the longest, so I twisted my head to lean back against the water. My chest was painful in the way it always was after I’d cried, and I felt it would be ill-advised to lose what freshwater I still had through tears. The strain in my throat grew heavier from keeping those tears suppressed. All the terror I’d felt last night—was it last night? Was it nights ago?—had gone; the water had taken me. The worst that could have happened had left already. I had passed through the aftermath of those dreams. The hand of the water had caught me and carried me away.

All I felt for perhaps the whole day, perhaps for longer, was grief, and a longing—for Amina, and for myself. I couldn’t discern one from the other. Neither of us had been alone in—how long? Almost twenty years, or at least not for those long, uncertain stretches of solitude in which the idea of finding one other person who could come close to understanding you is left in limbo. My heart circled and wheeled like an albatross through the open air, searching for some hint of her: some headland that recalled the sweep of her hair, or a pebble like the smoothness on the back of her hand, or some cloud that could gather the water from my body and give it to her.

***

On what I thought was the third day, I was dead. I had already died, or I would soon, before anyone found me, and it was better to think of myself as the equivalent of dead for now. The realisation was a quiet, detached one, a sequence of thoughts that clicked in place one after the other in a hidden recess of my brain.

I took to charting the skies. First a sequence of terns, the sharp angle of their wings distorting the terrifying bright blue. A squawking flock of plovers, a day or an hour or a few minutes later. It was to the gulls, with their virulently orange beaks and piercing cries, that I looked the most.

mila, you are the ocean, the gulls screeched, and I could not distinguish whether the soreness and tightness of my throat was from the salt I had swallowed, or the urge to cry with a body drained of living water. Pinned to the bobbing heads of the waves, I watched them wheel above, occasionally dipping down with their beady, fierce eyes, hitting the water with a harsh plunge. They blurred through the sky like clay smudges. What are your names? I asked them, and the sky, and the ocean. mila, mila, mila, they all cried.

***

Lying afloat on the water, as the sun crested over the horizon, the ocean was boundlessly suffused with light, golden hilltops emerging constantly out of each other. In my more optimistic moments, this was what death could be—the non-existence of any boundaries between the self and the world. I was not an intruder in these waters, any more than an oceanic current running courier between two continents; I was not flotsam or debris floating atop liquid histories foreign to me, spat out from the headlands, any more than the mild crests of waves. The moon dragged currents to shore and spun them back out again, holding me like a tight thread alongside them. My skin, pruned heavily by the first day, was no longer stable: it pinched and shuddered across the span of my skeleton in time with the tide.

It’s strange, how light and wind make tapestries out of running ripples of water. There is no such thing as a horizon: just an endless distortion of the boundary between water and air, each second an imperfect imitation of its previous iteration, already lost to the world that was a mere blink ago. If I tilted my head just so, I could see visions approximating the shapes of schools of fish. They were endlessly blurred and blessed by the water.

I was not acted upon by the world. I was not some passive subject, passed between sea and shore and wind and wave. Here, in a body I had never felt like I owned, I was a changing part of the ceaseless, unending world: I was a current, the shape of the water, I was light and sound and touch. I had a meaning in the language that gulls cried and fish gurgled and the setting sun whispered across the water, and that meaning shifted in my ears like the sound of Amina’s voice: mila, mila, mila.

At night, I could feel the water shift across the contours of what I had thought of as my body—not some strange, distant idea of Albert’s body, but mine: all of me, the thoughts, the beliefs, the minute shades of feeling. Every part of me moved and became the water. I could feel shifts in the pattern of skin across my body, a reconstruction on the geological scale.

Armored arthropods, in journeys lost for a million years, scuttled across their realm of early ocean water, buried themselves near receding shorelines, and were lost beneath aeons of sediment born of the slow falling and melting of rocks into waves. They were made dry and hollow, leaving only shadowy imprints in the layers of silt, pressed down and down into the earth by the carapaces of other trilobites, other ostracods, eurypterids’ segments, until they felt the lap of water at the rocks encasing them, millions of years later. From water, to land, to water again, an embrace a hundred-thousand years in the waiting.

I could feel my body reshaped in the same way, as though I had been buried on land and kept in a shell of silt and limestone and calcium; the water pressing at my skin’s edge was the memory of a home from before the world was made. I could return to my earliest home in a body remade.

***

In the sixteenth summer after my wife and I moved into the lighthouse, I became a woman.

IV

Like a piece of driftwood, I washed up on some shore, and lay there for hours on a bed of dessicated seaweed. I felt dried through. When I closed my eyes, blazing sun illuminating the pulses of blood moving in the veins of my eyelids, I could still feel the quiet rise and fall of the ocean beneath me, an unceasing motion just beneath my skin. I was not sure the water would ever leave me, and the idea gave me strength.

Around me, cicadas were buried at their legs in the wet sand, twisting their wings frantically to buckle their bodies in a series of slowing, slowing clicks: a fatigued attempt to escape from land. I sat up to pull them out, pinching the sides of their bodies to slowly wiggle them from where they were stuck. On the fourth one such creature I was extracting, the stomp of an impetuous white hoof sprayed sand over the struggling creature. Jericho—fur slightly ruffled and damp, but with the same suspicious slant to her rhomboid eyes. I stood to lift her, and looked across the beach.

At the end of this stretch of sand, Amina was rounding the last turn in the pathway down the promontory. She was never one for dramatics, so I was surprised to see her run, fighting against the draw of sand beneath her feet. Jericho gave an indignant bleat at seeing her, but she didn’t even spare the creature a glance.

In the open sunlight, Amina had eyes like she knew everything. Knew in the deepest sense, as though she had gone through some similar journey before: two trilobites, falling into the water one after the other. While half my soul was cast adrift, floating endlessly over the errant waves, the remaining half was easily tethered here by the crook of her finger beneath my chin and the slight breaking in her voice, like cresting seafoam, as she spoke: welcome home, mila.

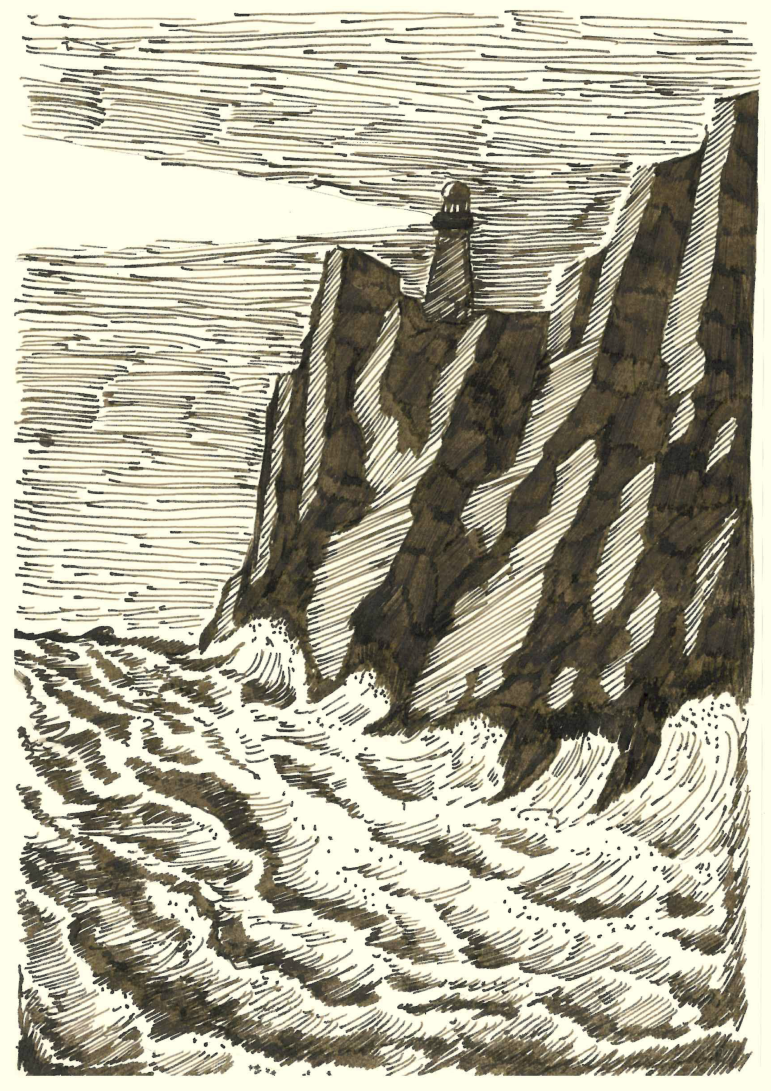

Illustration by Malaika Aiyar