1.

In the spare bedroom of a rented house

an old man lay dying.

His son had rented this house

for himself and his sister,

having left behind

his parents’ house

to seek work in the city.

None of them have been

home for many years.

Home is where mother,

the old man’s wife,

planted corn and tended to chickens.

Home is where the son

slipped out to the creek

and brought back niqiu

plucked from the mud

instead of homework.

Home is where they put

the new mahjong table

with its red felt trim

and everyone sat

and played and drank till dawn—

where everyone laughed and everyone fought

and everyone was friends again

when the sun came up.

2.

Home, now, has white-washed walls

and electric air conditioning. The son,

upon his return from the city,

paid for its renovation with his wife’s money.

His mother is pleased, although

she will miss the old garden

and the sound the rain makes on the roof-tiles,

but a nicer house means a longer stay

from her children, who had always complained

about the damp.

Now it is only her and her chickens.

She has a new brood now,

three weeks old but growing fast,

ready for slaughter when the grandchildren

come to visit in the summer. They phone her

once a month, give or take,

from their scattered cities,

about five minutes each time—

Yeah, I’ve eaten.

No, not as good as yours.

They don’t talk about the quiet,

the one thing missing from this home.

It has been missing, she knows,

for as long as they can remember.

But she is still waiting, though it has been years.

She is still waiting for the old man to return to her.

3.

The son is at his friend’s house playing cards.

The men are unaware of the sorrow hanging over his house,

and so they laugh without restraint. Still, the son,

despite his flight, cannot bring himself

to join in. He has always been a runaway,

skipping school for the cinema when he was a boy,

leaving his wife and children across the sea for his work.

Now, he leaves his sister at home, to wipe with a damp cloth

the forehead of a man who never raised them,

who had left them decades ago and returned only

when he knew it would be his last chance.

He told this to the woman he would come to marry

as they watched the sun descend into the sea.

Did you know, he said,

looking down at the grass,

My mother’s husband left her?

He left our house to sleep with another woman,

which drove my mother mad,

and so he had her tied up and sent away,

and there she was attacked, cut up all down her face

till she looked nothing like herself,

and then they stitched her back together,

and still he wouldn’t come home,

wouldn’t even look at her,

wouldn’t say anything?

The woman murmurs something inaudible.

I come from him, but he is not my father.

I will never become him.

(His phone rings; it is his wife,

who chides him for being out.

“I thought I would comfort you,” she says, coldly

“But it seems you need none,”

That is false, he thinks. I do need it.

I need you to tell me how to feel.)

4.

The old man in the rented house is dying.

This, he knows. It has been days

since he was able to keep anything down

or stand without assistance.

His children linger in the doorway.

Over the last few days they have watched him diminish,

from skin over bone to bone alone. Awake, still;

conscious, aware of it all, how he gags now even on water,

how he will not live to see the start of summer.

The hospital will not take him,

for there is no room, and little they can do;

and yet, the daughter thinks, it would be enough

simply to let him sleep. Let him pass peaceful

and unaware. Instead they have condemned him

to waste away in a foreign city,

slowly, lucidly.

It is too cruel, even for the son,

and that night when he puts him to bed

he calls him ba.

Visitors pour in the next day. The old man’s

brother and his wife, their children too,

cousins they hadn’t seen for years

stand with their heads bowed at his bedside

The old man stares up at the ceiling, his face blank,

silent unless they call for him, at which he makes a sound

to show he heard, and nothing more.

In the living room there is noise and chatter;

memories are cracked open and passed around the table.

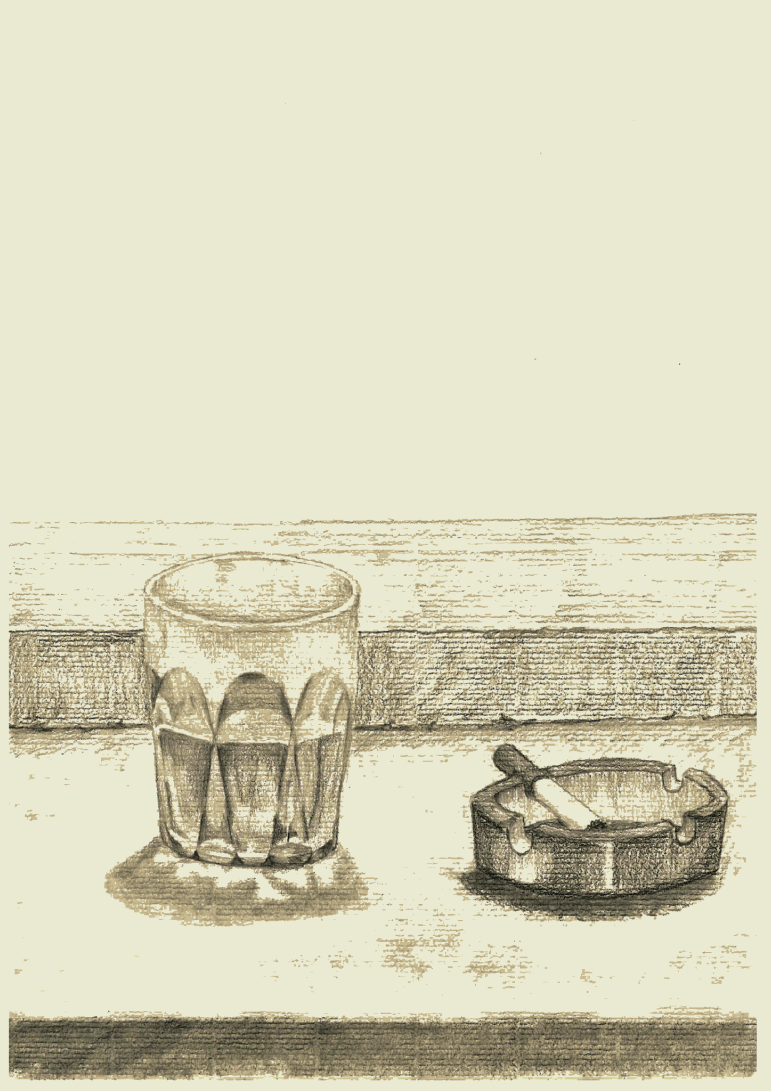

Someone pours out a bottle of baijiu. The son is not a drinker

but tonight he downs his glass.

The daughter leaves the room to smoke.

5.

When they come for his body they will say

he died at home, surrounded by his family.

This is true, if only in part,

and the old man will not be there to correct them.

He cannot tell them about Qian who missed the last train

and was coming down tomorrow,

or Yanrui who stayed behind

with his daughter too young to understand,

or how this place is not home, not really,

because home is a little house with a grey tiled roof

at the foot of Wawu Mountain, with chickens in the yard

and dacong growing in red lacquer pots

or at least it should be—

instead maybe it was a woman once beautiful,

sitting on a three legged stool outside the door

waiting for him to come home;

or maybe it was the city streets,

where golden lights shined like stars

and coin sang plenty in his purse,

and he knew the name of every corner,

every cobblestone beneath his feet;

Go back again, back further to a house by the river

whose shape he has long forgotten,

whose walls sheltered him once,

when he was too small to realise

he would lose this all, someday.

He cannot tell them how these places are not his,

not anymore, for he has been away

for a very long time, and now

he is gone from this place, too.

Illustration by Zander Fitzgerald